It's difficult to maintain a positive perspective when it seems you are book-ended by sirens of madness on one side and the encroachment of useless bullshit on the other. It makes one consider the benefits of a solitary agrarian lifestyle; unfortunately, that's not in the cards for me. Firstly, most solitary agrarians are often too invested in their solitude (and their agrarianism) to even stop and contemplate their identity - after all, occupational lifestyles such as "solitary agrarian" tend to come naturally to people. I admit I may have missed that boat. Secondly, I simply wouldn't trust anyone who identified him/herself as a solitary agrarian ("Take the chip off your shoulder, hippy." my inner pub-crawling bully yells out - let's call him Sully. Truth be known, he yells a lot).

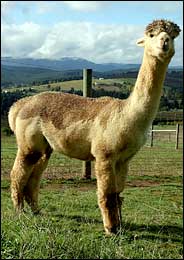

It's hard being an artist 1 when you're surrounded by a stream of people who also call themselves artists, not necessarily because they are or that what they do is particularly outstanding, but rather because it doesn't make your situation any easier. When you were a kid, an Artist was some sort of hallowed currency - you imagined they were raised on Easter Island by alpacas and shipped to the New World via hovercraft.2 Well, they're not. I suppose it's good that they're not, as I'm sure someone would've raped and pillaged them long, long ago, Viking-like. To that end, I'm thankful the world doesn't have to contend with a breed of sullen warrior sub-artists from Easter Island.

In the inner universe of the artist, "I" is the loneliest word. But let's come back to this.

On the extreme opposite of the universe, far, far away from the tiny satellite of "I" is "you".3 You, as in, not-the-artist. Sure, you could be "an artist" also, but it really doesn't matter. For all you know, they're nothing like you...or I, sorry. Bloody pronouns.

Right, let's come back to "I". Lonely word blah blah blah. Rudolf Steiner saw no difference between Art, Religion, and Science. In his eyes, they all dealt with the same conflict 4: bridging the chasm of understanding between the I and the not-I. Let's face it - everything around us is not us, and yet it is, and yet it's not. I have no relationship to the CBC Visitor sticker that I have stuck to the wall in front of me - it is, after all, a piece of sticky paper. Yet, it's an encapsulation of one of various meetings/sessions I've had at the broadcaster, which is tied to what I do for a living, which is somehow (sometimes depressingly) tied to who I am. There is a constant conflict between the inner and outer world and it is the job of the Artist, the Philosopher, and the Scientist to ask fundamental questions in order to better define this relationship. I suppose I could've picked a better example than a sticker, yes (Sully laughs in the background, a pint of Guinness in his hand, leaning back on his barstool, smoking a cigarette as only fictitious inner pub-crawling bullies can do in light of Toronto's recent smoking by-laws).

Every artist has to realise that they are, ultimately, alone. You can be part of a collective, you can have a gaggle of supporters, you can own an over-priced bar named Camera, but in the end it's your inner voice that expresses itself and not the sum of your distractions, be they good or bad. The environment - the "not I" - can inspire art, but it doesn't create art in and of itself. At best, in the Artist's World, the "not I" is a muse that we toy with, fight against, woo, or plunder jealously for material. But in the end, you're on your own.

I'm an unpublished writer (when I withdraw various insubstantial exploits: a College Street community newspaper that never got past Issue #1/Volume #1, a poem I wrote in high school that was somehow allowed in the Burlington Post, and various letters to the Globe and Mail), yet despite that, I'm not unaccomplished. This is the fine line: knowing the difference between a lack of commercial success and a lack of personal accomplishment. We tend to equate the two as synonymous, yet one is inherently more substantial than the other. I look back at the last five or six years and I say to myself ("Self...") that I've accomplished a lot (a novel, numerous short stories, countless poetry) - it's only been in the last year that I've begun to seriously aim for commercial success. I would rather be in this situation now than have peaked early (when I knew less about myself as a person and a writer) and withered, as most early-peakers do. Success is not a race, or at least that's what I tell myself when I feel I'm going nowhere.

The key is to forge on, and whether that requires optimism, humour, or even distilled anger is up to the individual. The common-sensical answer would be: whatever it takes.5

As for me today, I might just join Sully for a pint.

Footnotes:

1. I use the term "artist" in its general context. I do not specifically mean visual artists, although they are obviously part of the category. I just can't speak for them.

2. Hovercrafts. What kind of brilliant magic was that? Weren't they the coolest things ever made by mankind when you were a kid? Christ, give me a place with hovercrafts and moving sidewalks and I'm buying real estate.

3. This is assuming a finite universe which could contain opposite sides (which obviously wouldn't be possible if there was no end or beginning).

4. Conflict is, in retrospect, a slightly dramatic term - but I'm a slightly dramatic person.

5. The artistic process is just as important as the artistic product; it would be dangerous to focus on one to the exclusion of the other - you'd either be left with a industrious stream of mediocrity or constipated with directionless obsession. And you thought artists had it easy.